The use—and misuse—of deepfake technology is surging, and states are stepping up their efforts to combat deepfakes, especially with regard to election communications.

At the end of last year, I predicted this increase in legislation, as well as constitutional challenges to existing laws in Minnesota and Texas, both of which have materialized. In fact, it’s possible that the number of deepfake election laws passed this year could surpass 2024’s total, even with the possibility of federal roadblocks.

House GOP Propose Moratorium on AI Legislation

The House Energy and Commerce Committee on May 13 published a proposed amendment to the draft budget resolution granting $500 million to the Department of Commerce to modernize federal information technology systems using artificial intelligence.

Buried in this amendment was a moratorium prohibiting states from enforcing any law regulating AI systems, models, or automated decision-making systems for a period of 10 years. At first blush this proposal sounds radical—a panoptic ban on legislation concerning the hottest issue in the zeitgeist for a decade.

In practice, this proposal—if passed as written—may not have as broad of an effect on current and proposed state legislation as headlines would imply. The text of the amendment enjoins the enforcement of state legislation regulating “artificial intelligence models” and “systems,” but most state “AI” laws passed (and nearly all deepfake laws) regulate the use of such systems and impose no restrictions on the underlying models themselves. For example, a ban on enforcement of laws regulating the manufacturing of automobiles wouldn’t inherently preclude states from prosecuting traffic violations.

Furthermore, the amendment also includes a “rule of construction” provision clarifying that the prohibition won’t apply to state laws that don’t impose substantive restrictions on AI systems specifically, which many AI-focused laws do not. Generally applicable state AI laws that don’t single out AI systems are also excluded from the proposed moratorium.

To be sure, this proposal would hamper states’ attempts to pass comprehensive state AI laws targeting developers, but should leave tort-based laws regulating deepfakes largely unscathed.

Deepfake Election Laws Spread Amid Potential Ban

In the past two years, states have been swift to enact laws combating misuse of deepfake technology. Most laws target specific use cases such as electioneering and explicit image generation.

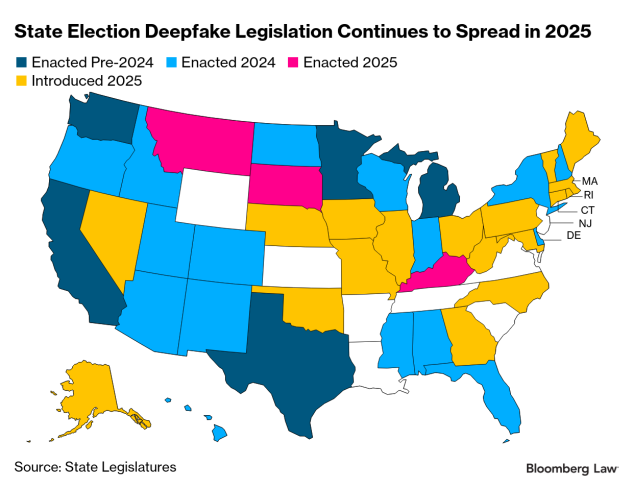

Before 2024, only five states had deepfake election laws on the books. By the end of 2024, that number jumped to 24, and this year shows no signs of slowing down. So far, three states have passed deepfake election laws in 2025, and an additional 18 have introduced legislation on the subject.

Most of these proposed laws don’t regulate AI developers, so they would likely remain unaffected by the moratorium should both pass. For example, North Carolina’s H.B. 934 prohibits people from using deepfakes to injure candidates or to harass, threaten, or harm individuals to influence elections. The bill imposes no restrictions on AI developers and even goes as far as to grant developers immunity from civil liability for errors produced by their AI products.

While there’s no guarantee that all—or even most—of the proposed deepfake laws this year will pass, midterm elections will be held next year. It’s likely that any failed legislation this year will be reintroduced or tabled for next year’s legislative session.

X Corp. Challenges Minnesota Law

On April 23, X Corp. filed a complaint in Minnesota federal district court challenging the state’s election deepfake law. The complaint alleges that the law is unconstitutional under the First Amendment, impermissibly vague, and is preempted by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

As I explained in my previous article, the Minnesota law stands out from other deepfake election laws in the way that it restricts speech, and courts are likely to find X’s arguments compelling. It’s one of the few laws of this type that imposes criminal liability on “persons” who publish content. While the deepfake law itself doesn’t define a person, Minnesota law more broadly includes corporations within the definition of a person. Criminal sanctions can have a greater chilling effect on speech, and courts are generally more cautious when reviewing speech laws that impose such a punishment.

Because the law restricts constitutionally protected political speech, Minnesota will have to demonstrate that its law passes strict scrutiny. This may be a challenge given the fact that there are less restrictive laws that X could point to in other jurisdictions that purport to serve the same stated purpose of protecting the integrity of elections.

For example, almost all state deepfake election laws include a disclaimer provision that permits the dissemination of deepfakes if they are accompanied with a disclaimer identifying the content as artificially generated. Minnesota’s law has no such provision, effectively operating as a complete ban on the dissemination of deepfakes within 90 days of an election.

In addition, Minnesota’s law doesn’t have a carve-out for parody or satire—a common provision found in about half of the state deepfake election laws. The law is limited to deepfakes made with the intent to influence an election, but that phrase could be interpreted as too broad to pass constitutional muster.

X could argue that most people engaged in political discussion online are attempting to “influence” the outcome of an election in the sense that they’re using speech to persuade others to vote for their candidate of choice, and satirical deepfakes are just another form of speech made to serve a broader point.

X also challenges the law under a preemption theory arguing that the law is preempted by the Communications Decency Act. About half of the state deepfake election laws incorporate section 230 immunity for online service providers. Minnesota’s law doesn’t, making it a target for preemption under 47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(1).

Texas Proposes New Deepfake Law

In 2019, Texas became the first state to pass a deepfake election law. At a total of 181 words, the law imposed criminal liability for the dissemination of deepfakes without a disclaimer provision or carveouts for parody or satire.

In my previous article, I predicted that Texas’ 2019 law was also a likely candidate for constitutional challenges. While the law was held unconstitutional by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, the Supreme Court of Texas never addressed the constitutionality of civil liability under the statute.

This year, the state legislature responded by introducing a new bill, adding more meat to the bones of the previous law. The proposed bill adds a disclaimer provision in the form of an affirmative defense, and includes a carve-out for specific types of AI-created media such as satirical cartoons, caricatures, and superficial edits to existing videos.

Even with these substantive amendments, the proposed bill falls short of other more narrowly tailored laws in other jurisdictions. While the previous law prohibited the publication of deepfakes within a 30-day window leading up to an election, the new law has no such time constraint and bans publication indefinitely. The proposed bill also remains silent as to section 230 immunities, making it a target for future preemption challenges.

With more deepfake election laws coming down the pipeline, the constitutional challenges are sure to follow. Should the proposed ban on AI law enforcement pass, many of these laws will likely remain unaffected, and state legislatures will have to draft their laws carefully to ensure that they only regulate users rather than the underlying models.

Bloomberg Law subscribers can find a variety of Practical Guidance documents, workflow tools, and reference materials for artificial intelligence on our In Focus: Artificial Intelligence page.

If you’re reading this article on the Bloomberg Terminal, please run BLAW OUT to access the hyperlinked content or click here to view the web version of this article.

To contact the reporter on this story:

To contact the editor responsible for this story: