Some tensions are emerging over the legal industry’s embrace of non-equity partnerships, as two lawyers sue firms this year over their status in the tier.

The lawyers suing Duane Morris and Thompson Hine allege they were underpaid and discriminated against. The non-equity tier was “a meaningless title more akin to an albatross,” a suing lawyer alleges. A former equity partner paid only a salary brought a similar suit against Lewis Brisbois Bisgaard & Smith.

The law firms are fighting the suits. “We strongly disagree with the allegations set forth in the complaint,” Duane Morris said in a statement. “We look forward to responding to those allegations and vigorously defending the case in court.”

What’s unclear is whether the lawyers will prevail, send shockwaves through Big Law and lessen the use of the tier that has boosted firms’ bottom lines. Conversely, solid wins by the law firms could boost their confidence in the classification.

The lawsuits so far point to the need for firms to clearly describe the benefits and burdens of the classification to rising partners, said Peter Glennon, a New York-based employment lawyer. “It’s not a one-size-fits-all partnership anymore,” he said. “These lawsuits are few and far between, but more may be coming.”

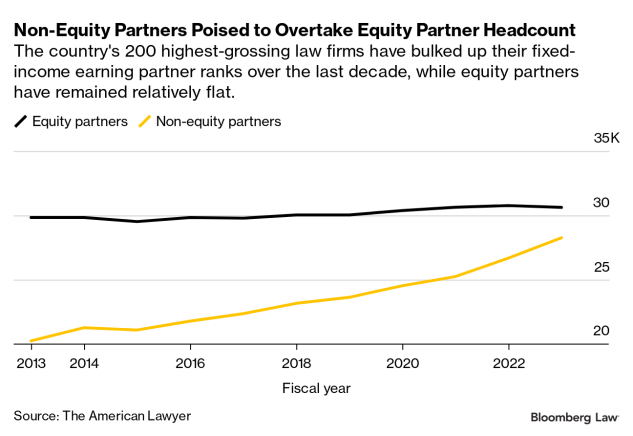

Law firms have grown their use of the non-equity partner tier to retain talent and boost profits for those at the top. Lawyers in the classification get the title and bill hours at higher rates than associates while foregoing large payouts that traditionally accompany partnership status.

Roughly 48% of nearly 59,000 partners at the 200 largest law firms last year were in the non-equity tier, up from 40% in 2013, according to American Lawyer data. During the same time, average profits per equity partner grew 90% to $2.24 million.

Firms “want to attract and keep folks who might not be appropriate for equity partnership,” said Nick Rumin, a New York-based legal recruiter. “Firms need to reserve equity for highest performing partners and to attract laterals. The more money that is available, the more that the firm can compete.”

Thompson Hine

Rebecca Brazzano, a former non-equity partner at Thompson Hine, sued the firm in February in the Southern District of New York. In her suit she describes the role as “an albatross” because she alleges she wasn’t able to share in the firm’s profits or exert influence over hiring or policies.

In her suit she said she should be able to bring discrimination claims under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. A court ruling that Brazzano was an employee and not a partner would “reverberate through Big Law and beyond in giving a voice to those employees who have been silenced by predator defendants under the guise that such protections are not available,” Brazzano said.

In a letter to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in February responding to her allegations, Thompson Hine said that as a partner, Brazzano wasn’t protected by Title VII. The firm said in a statement it does not publicly discuss its confidential partnership agreement.

Duane Morris

In a class action discrimination suit last month against Duane Morris, Meagan Garland claims non-equity partners are misclassified to “ensure maximum profitability and reduce business expenses and tax obligations for its equity partners by unlawfully shifting those burdens” to the lower tier. As a result, Garland claims her effective pay decreased after her promotion.

The firm shifted business expenses and state and local tax obligations to non-equity partners, withheld 18% of their fixed-fee compensation to pay down expenses and directed back to itself 4% of their gross annual compensation as a capital contribution, the complaint claims. Duane Morris stopped withholding employment taxes from her compensation and began assessing her a share of the firm’s state tax liability, reporting her compensation on IRS Form K-1, the tax form for partners, instead of a W-2, it claims.

The firm funded its political action committee with “unlawfully” deducted wages from non-equity partner compensation, supporting political contributions that are “made strictly with firm objectives in mind,” Garland alleges. She remains employed by the firm as an income partner.

Lewis Brisbois

In the lawsuit filed against Lewis Brisbois in April, Julie O’Dell alleges that when she was promoted to equity partner she was told she’d earn a set monthly draw for three years before she could receive profit distributions.

O’Dell, who left Lewis Brisbois in January 2023 to work for Armstrong Teasdale, alleges that the firm failed to tell her “that not all ‘equity partners’ were treated as true owners.” In addition, all “equity partners” weren’t treated equally for purposes of compensation, according to the suit.

Lewis Brisbois said in response to O’Dell’s lawsuit, “As is true for every equity partner at Lewis Brisbois, Ms. O’Dell was clearly informed of her rights and responsibilities in that role, as well as the compensation of each partner at the firm.”

To contact the reporter on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story: