- White House targeted judges, law firms, and DOJ in first 100 days

- Supreme Court showdown expected over executive powers

Lawyers choose their clients. Federal prosecutors need independence. And judges expect their orders to be followed.

Those foundations of the American legal system are being tested by President Donald Trump in his first 100 days back in office, with a barrage of moves exposing weaknesses that can be exploited by a powerful executive.

Trump is reshaping the Justice Department in the image of his own personal legal team and seeking to discredit—or even ignore—judges who rule against him. A Supreme Court showdown over the president’s powers appears inevitable, with Trump’s team eager to get final rulings on some of their top initiatives. At the same time, Trump has sought to sideline private attorneys that might otherwise join the fight by attacking major firms in a series of orders and striking deals with those that want to avoid the same fate.

“The president and his law officers are testing the outer limits of presidential power,” said Jonathan Wroblewski, a Harvard Law School lecturer and former senior Justice Department policy official. “The question for the second hundred days is how the appellate courts, and especially the Supreme Court, will see it and whether constitutional separation of powers is going to mean much.”

Trump calls himself the country’s “chief law enforcement officer,” signaling his broader view that the Justice Department answers to him, even if it has historically operated independently from the White House. The approach extends to courts, with aides arguing judges can’t check some of Trump’s immigration enforcement policies and the president saying he should be shielded from legal scrutiny.

“He who saves his Country does not violate any Law,” Trump tweeted in February.

Much of the strategy was laid out in the pre-election Project 2025 playbook developed by the conservative Heritage Foundation and authored by current administration members. The Justice Department section, written by White House senior counsel Gene Hamilton, envisions a strong executive to “restrain the excesses of both the legislative and judicial branches.” It also calls on department leaders to discipline government lawyers if they make litigation decisions that conflict with the president’s agenda.

The department under the control of Attorney General Pam Bondi has removed or reassigned dozens of career officials, including those in charge of units responsible for investigating public corruption and DOJ attorneys’ misconduct. DOJ is relying on a small group of political appointees in some of its most high-stakes court clashes, like closely watched cases over deportation policies in which federal judges have mulled contempt proceedings against administration officials.

Chief Justice John Roberts has already had to step in to rebuke attacks on judges, as some face calls for impeachment from Trump and Republicans in Congress. In one sign that the executive branch is still ramping up pressure on the judiciary, the FBI arrested a state court judge in Wisconsin last week. Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Hannah Dugan was charged with obstructing federal officials who tried to detain an undocumented immigrant scheduled to appear in her courtroom.

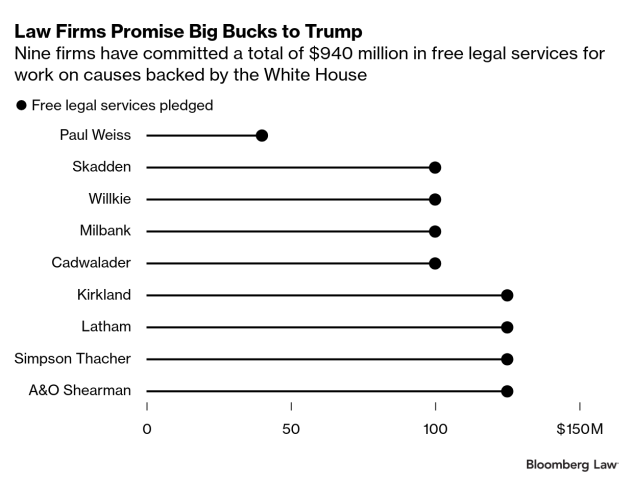

The White House’s war on Big Law firms was less telegraphed. Rather than going after individual lawyers, like those involved in the Mueller investigation and the Manhattan District Attorney’s suit against Trump, the president targeted firms with ties to the attorneys. He also scored nearly $1 billion in free legal services from nine firms seeking to avoid punitive executive orders against them.

“I don’t think we have had a president who seems so systematically determined to undermine the pillars of the justice system,” said Harold Hongju Koh, a Yale Law School professor who worked in the Obama administration. “He is disrespecting all of them. And in just 100 days.”

‘Activist Judges’

Trump’s second term in the White House has ushered in a new level of attacks on judges now reviewing the 130-plus lawsuits challenging the president’s raft of executive actions.

Trump administration officials have already flirted with defying some court orders in lawsuits related to the use of a wartime statute to deport alleged gang members to a Salvadoran prison without hearings. Drew Ensign, a political appointee overseeing the Justice Department’s office of immigration litigation, has argued both of those cases, a role that would usually be filled by career lawyers.

There has long been an assumption that government lawyers “are acting truthfully and in good faith,” said Marin Levy, a Duke Law professor who studies judicial administration. “The actions by government lawyers in recent cases undermine that presumption, the effects of which could be felt for years to come.”

A DOJ official said the department “will continue to vigorously defend President Trump’s agenda in court against unelected activist judges and are confident that we will ultimately prevail.”

The administration’s actions also recently prompted a sharp rebuke from Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson, a Reagan appointee on the Fourth Circuit. Wilkinson called the government’s position in litigation challenging the deportations “shocking” to Americans’ “intuitive sense of liberty” in a recent opinion.

“The friction with the courts will undoubtedly increase” in the ensuing weeks as judges issue final rulings, said Richard Donoghue, a former acting deputy attorney general during Trump’s first term who’s now a partner at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman.

At the same time, the administration’s “room for maneuver will decrease,” he said. DOJ lawyers must know there’s a “very high” price to pay, both politically and inside the courts, for flouting judges’ orders.

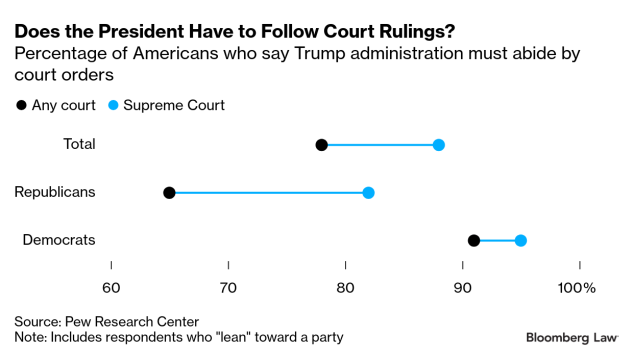

Seventy-eight percent of Americans believe the Trump administration must follow court rulings deeming administration actions illegal. That number rises to 88% if the ruling comes from the Supreme Court, according to Pew Research Center.

Trump and his allies have blasted judges and their family members while House Republicans have filed resolutions to impeach a handful of judges who ruled against the administration.

The spotlight on the courts ratcheted up concerns about the safety of federal judges hearing his cases. An implied threat: Hundreds of unsolicited pizzas have been sent in recent months to the residences of federal judges and their relatives, including some in the name of a New Jersey federal judge’s murdered son.

“In the past five years, you’d be hard pressed to find any instance in which 200 federal judges got a pizza anonymously sent to their home address in a very short period of time,” said Paul Grimm, a former Maryland federal judge who now leads the Bolch Judicial Institute at Duke Law School.

Retribution in Practice

On the campaign trail, Trump promised retribution against those who previously opposed him. In office, that promise has come with a twist: The president is overhauling a Justice Department he claims was “weaponized” against him while targeting the business of law firms that previously employed his perceived enemies.

The 154-year-old law enforcement agency is accountable to the president, but has over its history developed a culture of operating with some professional independence. It’s now led by a band of Trump’s former personal attorneys, including Bondi, deputy Todd Blanche, and DOJ official Emil Bove, who have set out to reshape the agency in the president’s image.

The Justice Department’s civil rights division revised its mission statements to align its work with Trump’s executive orders, while the president’s choice to lead the DC US attorney’s office has referred to his office as Trump’s lawyers.

Bondi mimics Trump’s ire toward the federal bench. “These judges obviously cannot be impartial, they cannot be objective,” she said during a Fox News appearance in March, referring to courts blocking various administration moves. “They are district judges trying to control our entire country and they’re trying to obstruct President Trump’s agenda.”

In one of the cases where contempt proceedings are under consideration, the department removed a longtime DOJ immigration lawyer from his role. The move came after the attorney told a judge that the administration had yet to give him a “satisfactory” answer on why the US could not return a Maryland man mistakenly deported to El Salvador.

White House spokesperson Harrison Fields said that Trump “cannot be more clear in stating that his Department of Justice will act independently of the White House and any assertion otherwise is a lie.” Trump is “incredibly supportive” of Bondi’s actions “to restore the integrity of the DOJ and realign its mission to promote Law and Order, uphold the rule of law, keep our country safe, and protect civil rights,” Fields said.

Trump has, meanwhile, targeted firms such as Perkins Coie, seeking to cancel its clients’ government contracts and to bar its lawyers from accessing federal buildings and interacting with federal agencies. That punishment came despite the firm no longer employing the lawyers Trump’s order admonished—a pattern common to other firms he has targeted.

The strategy proved successful. In a court filing just a week after the order was issued, Perkins Coie said government employees informed its lawyers they couldn’t attend scheduled meetings, and some clients either quit or told the firm they were concerned about continuing to work with it. Perkins Coie is fighting the order in court. Like three other firms target by Trump, it won a temporary bar on much of the order’s implementation.

To many in the legal industry, the campaign against Big Law isn’t about retribution. It’s meant to show there’s a clear threat associated with challenging the president.

“The message to the bar is: Watch out,” Paul Clement, a star conservative litigator who’s representing WilmerHale, told a federal judge in court. “You can’t practice law in that environment.”

Since striking a deal with the law firm Paul Weiss, Trump hasn’t even had to issue executive orders to have eight other firms fall in line—highlighting the industry’s fear of being marked by the administration.

A group of 700 partners at major law firms filed an amicus brief urging a federal judge to strike down Trump’s executive order against Susman Godfrey. They said they had observed “many lawyers” declining representations they otherwise would have taken out of fear of retaliation. The group also said clients have hesitated to hire law firms that could become the president’s “next target.”

“The orders are having their intended effect,” they said.

‘Big Test’

Trump still faces challenges to his administration’s major policy goals, including from some of the largest law firms.

Akin, one of the country’s largest firms, in mid-April filed a lawsuit challenging the Trump administration’s emergency tariffs as “an extraordinary Executive Branch power grab.” Pratik Shah, an Akin partner who leads the firm’s Supreme Court practice and has argued more than a dozen cases before the top court, signed the lawsuit on behalf of a small educational company.

Other leading firms, such as Arnold & Porter, Gibson Dunn, Quinn Emanuel, King & Spalding, and Perkins Coie are also taking the administration on in court.

It’s too soon to tell if Trump has taken top law firms off the playing field as courtroom opponents, said Lauren Rikleen, executive director of Lawyers Defending American Democracy.

“If these major firms are afraid to take on clients who have matters against the government, that is a huge impact,” Rikleen said. “You can’t save the rule of law and democracy if you can’t have a fully functioning justice system, including lawyers who can pick whatever clients they want without punishment and function in the courts without retribution.”

Yale’s Koh said it’s ultimately up to the Supreme Court to decide how far the president can go.

“He is bending independent prosecution to his political will. He is oppressing the legal opposition by going after their ability to represent opponents to his positions. And he’s trying to intimidate judges who might rule against him,” said Koh. “And it is all building up to a big Supreme Court test.”

To contact the reporters on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story: