- Government-backed payout close to ‘a sure thing’

- Tens of thousands of claims building in NC

Litigation funders are pouring billions of dollars into the Camp Lejeune toxic water cases, lured by the possibility of hundreds of thousands of claimants and a payout backed by the government.

A consultant who collects data directly from industry participants says lenders have already committed nearly $2 billion to firms filing Camp Lejeune lawsuits, and estimates at least one-third of all the claims will ultimately be backed by litigation financiers. A law firm hoping for a lead role in litigating Camp Lejeune cases was seeking a loan north of $50 million, one funder said.

The growing litigation-funding industry has increasingly turned its eye toward mass torts that hold the promise of large payouts, and the Camp Lejeune case is poised to be among the biggest ever. The government has projected it might ultimately shell out $21 billion to compensate the veterans, workers and their families sickened by contaminated water on the U.S. Marine Corps base in Jacksonville, N.C.

The Navy, which oversees the base, has already logged 75,000 claims, but has been slow to process them. Veterans whose claims are denied or unresolved six months after the filing can sue for compensation in North Carolina, where court officials are preparing for at least tens of thousands of lawsuits.

“Nothing in investing is a sure thing, but when you’re looking for a sure thing, this is kind of the closest you can get to it,” said Rebecca Berrebi, founder of Avenue 33, a New York-based litigation finance consultancy.

A New Way

Litigation finance began appearing in the United States in the early 2000s, but has exploded in recent years as funders raked in high returns.

Initially, many invested in single, business-to-business cases that only paid out when the plaintiff was successful. But the scope of targets has broadened, and the loan conditions have become more variable.

Details about the investors backing litigation funding is not public, but funders say they are often institutional investors, family offices, and high-net-worth individuals.

Critics of the trend have warned that it could give anonymous funders an outsized influence in the outcome of a case.

More funders these days are focusing on the mass-tort sector and financing personal-injury law firms with loans that have double-digit interest rates, sometimes above 20 percent. They typically issue loans to firms against their entire portfolio of cases, which is considered a safer bet.

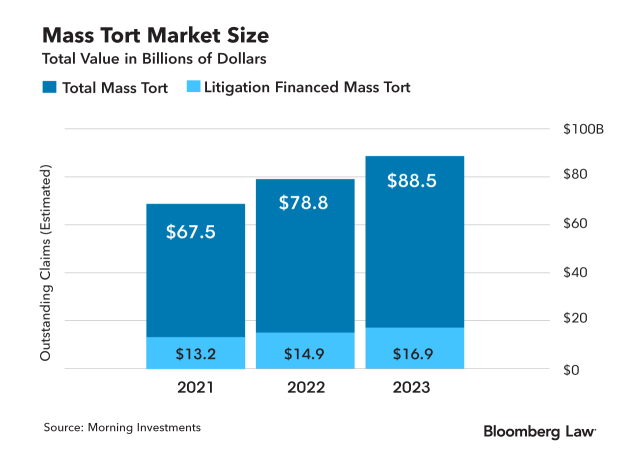

“It’s arguably more attractive in that there’s less risk and less volatility in that return stream,” said Michael McDonald, partner at Morning Investments, which provides research, advisory, and valuation services to alternative investments including litigation finance. “The level of focus on portfolio funding has grown enormously over the last five years or so.”

McDonald’s firm’s data show that financing in mass tort claims has steadily increased in recent years, and that funders poured more than $16 billion into the sector so far this year.

Camp Lejeune claims have emerged as a popular investment, with around $2 billion committed, his company’s research suggests. The toxic-water cases are “saturated” with funding, McDonald said, and the investment value could be waning.

“There’s a variety of issues that can come up here, but in general, as you get to a later stage, the values tend to trend lower on average,” he said.

Case Work and More

The loans support the actual case work by firms, or go toward claims acquisition firms that sign up clients using advertising. Law firms and legal marketing agencies spent more than $145 million on advertising last year in a bid to recruit potential Camp Lejeune victims, Bloomberg Law determined.

Litigation funding has drawn criticism because of its opaque nature and the inability to easily identify who is financing legal efforts. Wisconsin, Montana and West Virginia are among the first states attempting to force disclosure; others are considering similar guidelines.

The Clerk of Court in the Eastern District of North Carolina, which is managing the flood of Camp Lejeune lawsuits, declined to say whether the judges there are considering requesting such disclosure for law firms in the case.

Without disclosures, one of the few ways to identify litigation funding is Uniform Commercial Code filings, required by uniformly adopted state laws and designed to identify transactions between two entities. But even then they only show that a law firm has borrowed money from a funder—not the amount or the reason.

Funders often must file UCC filings logging their loans.

Their recipients are typically hidden behind registered agents, but UCC filings show litigation funders loaning money to at least three firms active in Camp Lejeune cases: TorHoerman Law, an Illinois-based firm; Milberg, which is based in Tennessee with offices in the U.S. and internationally; and the Bell Legal Group, a South Carolina firm that lobbied heavily to stop Congress from limiting attorneys’ fees in the toxic-water litigation.

Glenn Phillips, managing partner at Milberg, said he could not discuss specific funding or recipients, but acknowledged the firm has been retained by a significant number of Camp Lejeune clients.

“Milberg periodically will engage in litigation finance if they believe it’s in the best interest of the client(s) when litigating against large well-funded corporate entities,” he wrote in an email to Bloomberg Law. “Many of the cases handled by Milberg can be large and complicated matters involving an enormous amount of expense for retaining experts, taking depositions, and other related litigation expenses.”

Deer Finance, a funder with a lien to Milberg, did not respond to requests for comment.

Tor Hoerman of TorHoerman Law said in an email that the firm has consistently used bank financing for its operations on torts and cases.

“This is absolutely nothing new or specific only to Camp Lejeune,” he said. “I do not have Camp Lejeune litigation funding. My firm did not ‘take a loan’ outside of its normal course of business.”

Though the industry has come under scrutiny, litigation funding also gives plaintiffs and lawyers more resources and room to dive deeper into cases, whether through identifying more alleged victims, gathering evidence or investigating discovery.

Ted Farrell, founder of Litigation Funding Advisors, said filing claims like the Camp Lejuene lawsuits can be time-consuming.

“Much of this third-party funding is being done to actually work up these cases such that these claim holders can actually get compensated,” said Farrell. “Each case is a tremendous amount of work.”

Court records and UCC filings show Bell Legal Group has received financing from at least two litigation funding firms: Arizona-based Pravati Capital and Rocade Capital in Northern Virginia. Rocade also has a lien with TorHoerman Law.

Rocade provides loans to law firms ranging from $10 million to over $100 million.

Its CEO, Brian Roth, said a loan to a firm like Bell Legal Group is atypical for his firm, since Bell is primarily focused on one mass tort. But given the contours of the case, and the government’s concession that the base waters were contaminated, Roth suggested it’s a good investment.

“Bell has been involved really longer than probably just about any firm at scale in the market,” Roth told Bloomberg Law in an interview. “We don’t know what the government is going to do here, so there’s a lot of uncertainty in how this is going to play out versus a traditional product liability space. But we’re not facing the same sort of corporate profit motive.”

Bell’s founder and senior partner, J. Edward Bell III, previously told Bloomberg Law he has spent as much as $15 million and more than a decade on behalf of Camp Lejeune veterans. And on Wednesday, the judges overseeing the litigation named him lead counsel in the case.

In an interview Wednesday afternoon, Bell wouldn’t disclose how much his firm has borrowed. He said the firm’s work with Rocade has been “extremely beneficial” but that his loan was no different than getting “inventory financing” for a clothing store.

“Sometimes you’re busier than other times and you need a little bit more money. Sometimes you aren’t,” Bell said.

Pitches and Skeptics

Critics of litigation finance cite fears that funders will play too great a role and influence the litigation outcomes.

Earlier this year, food supplier Sysco Corp. sued litigation funder Burford Capital, alleging the funder halted the company’s attempts to settle price-fixing claims. Burford had provided $140 million to pursue the antitrust litigation.

Bringing the dispute to an end, Burford is now seeking to become the sole party in the case by creating a limited liability company and filing a motion for the company to become the plaintiff. Antitrust claims can be reassigned.

Another Arizona-based funder, American Law Firm Capital, has been pitching loans to law firms who might consider bringing Camp Lejeune lawsuits, predicting that the settlement payoffs could be five to 10 times the amount they spend on the cases.

The firm’s promotional materials, obtained by Bloomberg Law, say that most loans the company advances are worth $10 million to $250 million or more with interest rates ranging from 10% to 18%. The company didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Some funders are skeptical of the Camp Lejeune payoff. Lisa DiDarioof C Cubed Capital Partners says her Florida-based company was approached last year by a representative of a law firm requesting more than $50 million for Camp Lejeune claims, but her company passed.

DiDario says that though there is a government-backed payout in the litigation, it is difficult to accurately value the claims since there’s no clear sense of how long the cases might drag on.

“It is a sure thing, but the amounts and the timing is still to be determined,” said DiDario. “Those funders that invested money in it, especially early on, they’ve still got a couple more years in which to continue that ride.”

The Camp Lejeune Justice Act, enacted by Congress and President Joe Biden last summer, approved compensation for veterans, their relatives and workers who spent at least a month on the Marine base between 1953 and 1987 and blamed its tainted water for their cancer, Parkinson’s or other diseases.

About 1 million people were potentially affected, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs. All claims have to be filed by Aug. 2024. If a claim is denied or unresolved after six months, those affected can file suit in the Eastern District of North Carolina.

The pace of resolving the cases—few if any claims had been settled by the end of June, nearly a year after the law was enacted—had outraged lawyers and veterans who said they needed the compensation to pay for their treatment. About 1,100 claimants have already taken the dispute to court. All claims have to be filed by August 2024.

Jerrold Parker, a founding partner at Parker Waichman LLP, a firm representing for Camp Lejeune victims, said the litigation is attracting funders because it’s a good bet.

“The way the law that passed was written, it makes the recovery extremely likely,” Parker said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Emily Siegel in New York at esiegel@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

and

and